The Mason's Trouble And The Scott Monument

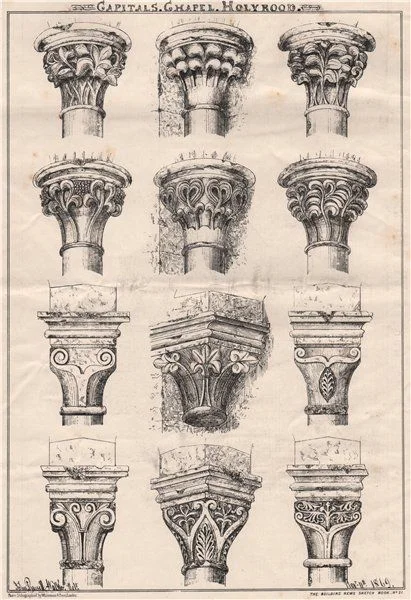

/Image: Ebay slide, 1840s.

This well-known image of stonemasons carving a griffin destined for the Scott Monument was taken by the famous photographic duo Hill and Adamson in the 1840s. We adore this photo for the fact that it shows those who walked in our stonemasonry boots half a century before our business was set up, working on one of the finest edifices in the country.

The photograph is very obviously staged , with a cluster of stonemasons gathered around a single block of Binny sandstone, their mells, chisels and other tools on display. However, this does not detract from its beauty and the photo piqued my interest to find out a bit more about the life of stonemasons in Edinburgh during those times.

What I found out was shocking. I quote verbatim from an article from The Morning Advertiser, dated Friday 25th March, 1853:

"Mortality Among Masons

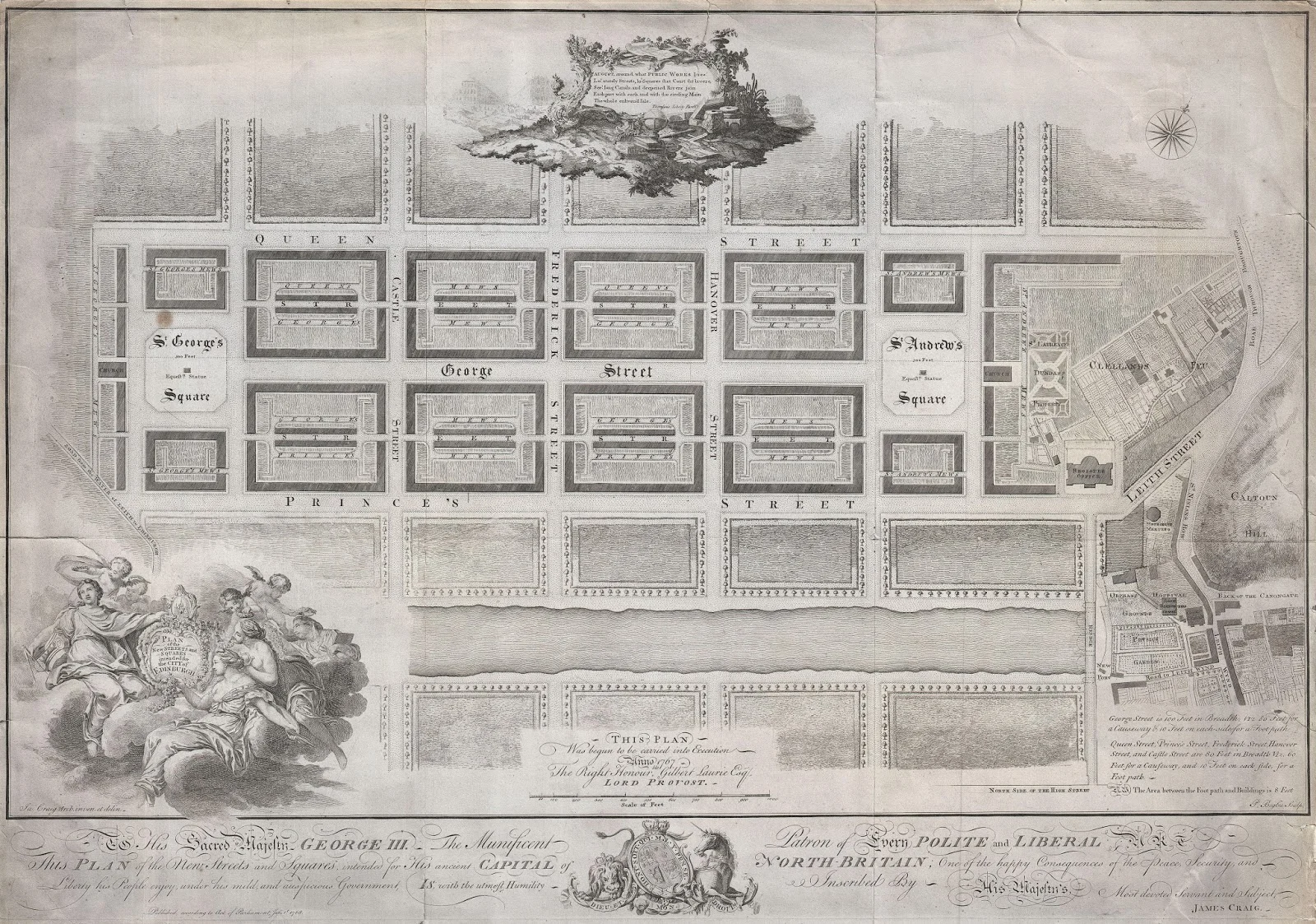

Masons are continually surrounded with an atmosphere of fine, impalpable dust. By the ordinary act of breathing this dust is received into the air passages and the lungs, where it slowly accumulates. Inflammation supervenes - slight at first, it is ultimately acute. A wasting then begins, accompanied by spitting. In a short number of years a mason dare not walk sharply up a hill....General debility is then felt - rapid consumption occurs - and at length the disease which originated in his apprenticeship terminates with his premature death. This is the disease known as the "mason's trouble". It is termed phthisis in medical phraseology...Dr Alison has said that "there is hardly an instance of a mason regularly employed in hewing stones in Edinburgh living free from phthisical symptoms to the age of fifty." We can go lower than that: we can state from pretty extensive observation that there are none but suffer from it at forty. We do not, in truth, know ten hewers (working) in Edinburgh above fifty and only two at sixty. It is to be observed, however, that the celebrated Craigleith stone, of which the New Town of Edinburgh was built, contributed more largely to this characteristic disease than the softer stones at present in use. An old Craigleith man was done at thirty and died at thirty-five. Out of twenty-seven apprentices - fine, healthy young men - who began with Forsyth at the erection of Cramond Bridge, twenty-six years ago, only two survive. Out of 120 hewers who worked at the High School in '27 we know of only ten survivors. In a squad of thirty stout hewers who began the Edinburgh And Glasgow Bank twelve years ago only half survived to see it finished. The stone-cutting and carving of the Scott Monument killed twenty-three of the finest men in Edinburgh. The stones, let us humbly suggest, might be worked damp and, we are informed, worked better. The sheds too might be better ventilated. The men had better endure the wind and rain, the storm and tempest in their greatest fury than endure for a single week the atmosphere of a shed. Another corrective has been pointed out by Dr Alison, who recommends the hewers to wear moustaches and beards. It is a notorious fact that cavalry regiments suffer less than regiments of the line from consumption. Their beards and moustaches act like a respirator: and the same line of reasoning applies with greater force to stone masons. In the south of Germany...where freestone is extensively worked, and where the masons are fine-looking, muscular fellows with large beards, such a disease as pthisis is never heard of."

Thankfully, things move on and Health & Safety now requires all stonemasonry companies to comply with strict regulation to ensure that their employees' health is no longer compromised in this manner, and employees are given all necessary equipment and training to ensure that they too can look after their health at work on an ongoing basis. Scott & Brown are proud to have helped create a new type of shed extraction system in conjunction with the Health & Safety Executive which became a benchmark for future extraction systems within the industry.

From where we stand now, we can only look back at the working conditions of the past and be grateful for change. When we look at the grand buildings around us we often forget of the human cost which came at a time when labour was cheap and plentiful but was all too often lost and forgotten, leaving behind impoverished wives and children eking out a living on the breadline. I only hope that the men shown in the photo made it through and that the next time you stand in awe of our architecture you remember those dusty souls of the past who laboured their lives away in creating beauty from stone.